I’ve admitted many times that the final straw that opened my heart to the truth of the Catholic Church was the reading of Saint John Henry Cardinal Newman’s two classic books: his Apologia Pro Vita Sua and particularly his Essay on the Development of Doctrine. His example and then challenge to become “deep in history” led me to a much more deliberate reading of Church history, and particularly the writings of the apostolic fathers. As a result, his “warning” became true in my life: I “ceased to be Protestant”, and my family and I entered the Catholic Church in the winter of ‘92.

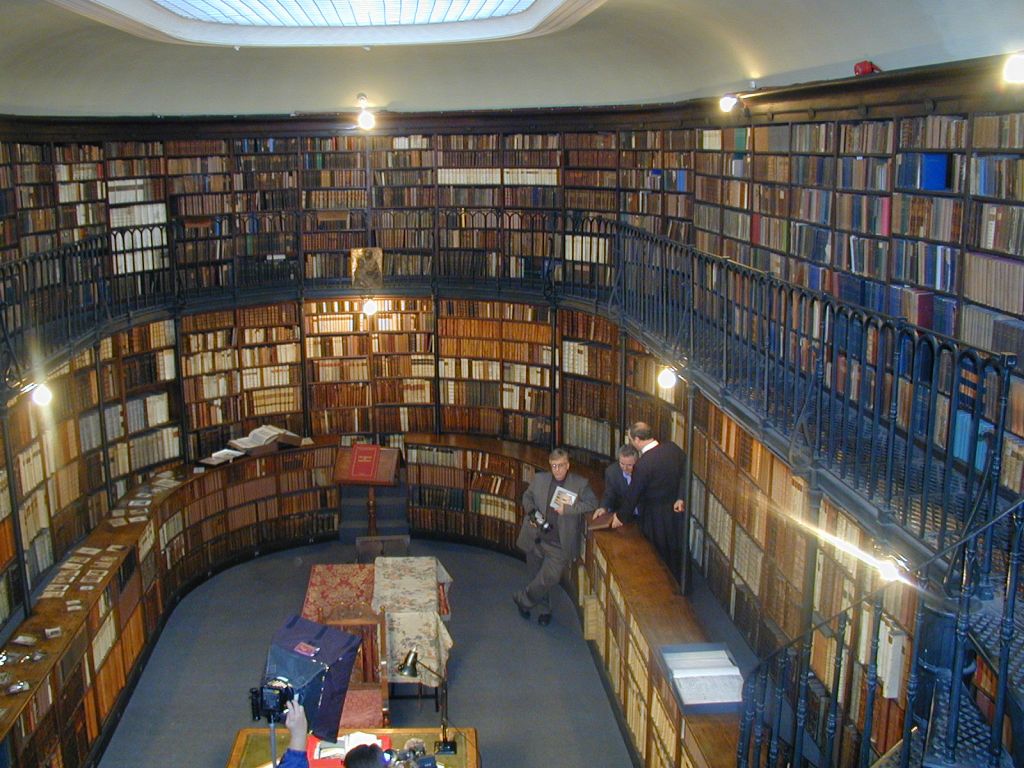

His charge to become “deep in history”, however, didn’t end there. This challenge not only became the mandate for my life, but in some sense an obsession. Over these past 30+ years, I’ve read more books on the histories of every aspect of our Christian faith and tradition, by Catholic as well as non-Catholic authors, then our local libraries can hold. The end result, as I now sit in supposed “retirement” in my “cabin in the woods”, with my wife and 4 cats, is that I’ve discovered, with great trepidation as well as grace-filled relief, the danger of becoming too “deep in history”.

To steal an oft used metaphor, studying history can be a bit like peeling an onion. The first few layers help one clearly discern that it is an onion, what kind, whether it’s healthy, et cetera, but the deeper one continues peeling, one gathers little new usable information, until when the last peel is removed, what does one find? Nothing, but a pile of detached skins.

What I’ve found from 70+ years of studying history, admittedly with an accelerated intensity, is that the process does not necessarily lead to one, unified, definitive conclusion, like modern physicists dredging tirelessly for one Unified Theory to explain all of life. This is because in-depth historical study does not necessarily uncover new, actual historical facts. Rather, because historical facts come to us as baggage on the transports of historical opinions, we can end up with far more unanswered questions than when we began.

There’s a tricky balance here. Certainly some historical research is essential, even necessary to clarify the soundness of one’s present position. In my case, as Newman quipped, to become deep in history was to cease being Protestant. But I also found that to continue becoming deeper and deeper in history does not necessarily lead one to become Catholic, or even Christian, as evidenced by the myriad of non-Catholic Christian and non-Christian historians who are far deeper in history than most of us will ever hope to be. This does not mean that Catholic Christianity is untrue. The danger is that one can become dangerously overwhelmed by conflicting yet seemingly well-grounded opinions, even about many things we once considered incontrovertible historic facts—like the resurrection of Christ or even His historical existence. In the end, one can become left alone to search for truth in the cacophony of conflicting historical opinions, all of which are from historians far more equipped to explain history than most of us.

There’s one thing that has long been understood about the many Ecumenical Councils of bishops held throughout the past two thousand years: that it’s the final decisions and declarations of these Councils that carry the authoritative guidance and protection of the Holy Spirit, and consequently require the faithful affirmation and obedience of the membership of the Church, and not the Councils’ inner workings, debates, and controversies. Countless volumes of books have been published detailing the inner politics and wrangling between the parties of attendees for all and every Council, and these sometimes secret revelations can be quite fascinating. These analysis, however, are sometimes used to explain or qualify, even explain away, the unpopular declarations of a Council. The danger is that one can be drawn to see the Councils as nothing more than the horizontal power plays between human combatants, ignoring the vertical influence and guidance of the Holy Spirit. The end result can be a doubting of the reliability and divine authority of a Council’s conclusions. This has certainly happened for many Catholics and non-Catholics in relation to the conclusions of both Vatican I and II, as it was for the conclusions of Nicea seventeen centuries ago.

What I have concluded is that this is equally true for the study of history in general. It’s obvious to suggest that thousands of volumes of world and Church histories have been penned, and though some insist that history is, in fact, “His Story”, still, almost all tell history from a predominantly horizontal human perspective, even at times bordering on Deism. The danger is that the more one becomes “deep” in the intricate details of history—especially through the myriad of lenses used by the myriad of historians—one might be tempted to question, not only the legitimacy of once previously assumed historical facts, but also of one’s Church, even the legitimacy of one’s faith. And the devil laughs, leading to the continuing increase of Christian traditions, as well as the unfortunate exponential increase of “nones” in this crazy twenty-first century.

Amazingly, this is true of the deep research into almost any historical topic. The more one digs, whether it is into the history of farming or economics or football or knitting, the more one accumulates increasing, unanswerable questions.

If one insists on reading deep into history (as frankly, given all I’m pontificating about, it’s close to impossible for me to resist because I love studying history!), it seems one should focus as much as possible on primary sources, rather than secondary or tertiary historical commentators. The problem, though, is that most early primary sources have only come down to us through translations, which in turn can carry the historical bias of the translators. For example, Irenaeus’s monumental classic, Against Heresies, has many complications, both in producing an accurate compilation of what remains of the original document, as well as an unaffected translation. So, even in studying the earliest Church fathers, one must be guarded and cautious.

For example, one complicated and precarious historical question is how the New Testament witness to the early structure of the Church based on apostles, prophets, overseers [episcopoi], elders [presbyters], and servers [deaconoi], evolved into an Aaronic-like sacramental economy of sacerdotal bishops, priests, and descending orders of deacons (i.e., the early Hebrew Christians all understood, from centuries of experience, the clear distinction between an elder/presbyter and a priest/hiereus). The more one digs into the historical records, the more questions arise. One does not easily find a definitive moment or event or declaration when this transition was explained or defined. This is essentially why Newman’s own historical research (to explain why there was such a difference between the Church of the first centuries and the Church of the eighteenth century) concluded in a somewhat nebulous yet carefully defined theory of development. He was not necessarily encouraging the querulous use of his theory to dig deeper to either prove or disprove the development of a later doctrine, but rather to thereby trust that the doctrines now defined and defended by the Church have in fact been legitimately guided by the Holy Spirit, and to trust that any new developments defined by the Magisterium of the Church will carry the authority and guidance of the Holy Spirit. Like in the study of Church councils, it becomes far more trustworthy for us to trust that God has been guiding and continues to guide the Church and world history, then to analyze, study, and debate over the process.

By His grace, the basic study of history brought me home to the Catholic Church. This must remain, for me, the foundational truth for any further study of history, for daily living, and for any understanding of the future. To abandon this foundation, through a continually deeper self-driven study of history, will possibly bring me, not to an ever clearer definitive answer, but deeper into the center of an onion: to nothing. This is why the blogosphere runs rampant with self-assured historians, theologians, philosophers, and self-proclaimed “influencers” who, though once grounded in their Catholic Christian faith, have now “seen the light” through their own becoming “deep in history”. Putting aside and ignoring the guardrails established by the successors of the apostles, guided by the Holy Spirit, these well-meaning men and women have journeyed further and deeper into the uncertain, unsteady reign of historic onion skins.

In the end, none of this can necessarily be argued or proven by reason to those outside the Church. I can envision the reams of arguments I might receive from the non-Catholic historians and authors I’ve read, as well as the dozens of old Protestant friends and classmates who, in the end, were not drawn home to the Church through their own reading of history. Rather, in the end, this all remains far more a matter of faith than reason, trusting that the Lord continues to “be with” the Church He established in His Apostles, as He promised, guiding and guarding their successors in union with the successor of Peter.

I would say, as I sit retired before my fire, it’s not so important to continue becoming deeper in history, or even deeper in Scripture, but deeper in the rich teachings of the Church, especially when it comes to growing by grace in Christ, through humility, obedience, and love.

Leave a comment